Program Notes

In the Clearing by Kenneth Fuchs (1995)

“What a joy it was to compose In the Clearing for Coro Allegro. I first had the pleasure of hearing the group perform at Church of the Covenant, Boston, Massachusetts, in May 1994. I was deeply touched by their musical sensitivity and sense of community, and I decided then and there that I wanted to compose a complete cycle of a capella choruses based on Robert Frost texts for them. As I worked through the following fall and winter, Coro Allegro’s sound and musical spirit were an ever present source of inspiration.

Robert Frost’s lovely poems are ideally suited to Coro Allegro’s gentle sensibility. On one level this selection of poems is about nature and a walk through the seasons, fall to spring. On another level, they are about the impermanence of the world around us and, perhaps, the uncertainty we often feel in our relationships to other people and the things we cherish.

Coro Allegro presented the world première performance of the complete cycle at Church of the Covenant in Boston on May 20th,1995, [thirty years ago and] exactly one year to the day that I first heard them perform. It is with much affection that I composed these choruses especially for them.”

—Original composer’s note by Kenneth Fuchs

For Coro Allegro’s video documentary Devotion: A Celebration of GALA Choruses, Kenneth Fuchs spoke further with Artistic Director David Hodgkins about the impetus for the work and Coro’s mission as Boston’s LGBTQ+ and allied classical chorus:

David: “I remember that you talked about how the cycle of In the Clearing is also a metaphor for coming out, especially the 7th movement, “A Young Birch.”

Kenneth: “Because I was so moved by the mission of Coro Allegro, I thought, I want to find a set of poems that reflects that, but also underscores in a beautifully literary way the group of people who comprise Coro Allegro, what their lives are about, what the mission is, and what it is to really stand up and be yourself and how challenging that can be. Of course it’s rewarding too.”

Kenneth: “Devotion” and “Nothing Gold Can Stay” are truly personal favorite pieces of mine. “Devotion," the poem, has that wonderful kind of reductive Emily Dickinson quality about it. It’s like a rock. I love that poem I really do.”

David: “I love the setting. I love the poem too. But the setting is so beautiful because it’s like time stands still and things slow way down.”

Kenneth: “The last line of the poem talks of “counting an endless repetition.” And for those listening, the idea of taking the word “counting” and scattering it in different rhythmic transformations through the chorus as a repeated word felt like absolutely the right thing to do.”

David: “It was especially poignant considering that the AIDS pandemic was at the same time, and so that last movement, “Nothing Gold Can Stay” resonated with so many people.”

Kenneth: “As we are talking about this, I can still see in my mind’s eye, the two performances at the GALA Choruses Festival in Tampa, FL in 1996. The Coro Allegro performance was one of the few in that whole series of concerts that was a serious classical cycle. I remember when the chorus finished “Nothing Gold Can Stay,” after all eight poems. The audience jumped up and started screaming and cheering and stomping. It brings tears to my eyes to think about it. It had such a powerful impact on that audience and I was so proud of that, because I knew they got the message and that’s exactly what I wanted the piece to do.

“I was so proud that you programmed this work at GALA. I’ve been thinking about other composers who are also advocates for their sexuality. And of course my mind immediately goes to Ned Roram, whose music I love, and who is in fact a dear friend…I want to be known primarily as a composer, but I can’t ignore the fact that I have a responsibility as an artist to bring something forward to the life I live as a Gay man…So every so often, when the piece is right or the opportunity to write a piece feels like it is something I can do to promote the cause, it’s something that I do, because artists have a social responsibility.

“I feel that way about In the Clearing. It was a privilege to write it for Coro Allegro but it was just so clear to me that the piece somehow had to embrace the Gay, the LGBTQ experience. Since 1993-1994 when we first worked on the piece, the opportunities, and certainly also the challenges, and the growth and transformations of what it is to be individually yourself, comfortable in your own sexuality and the expressions of that have grown so enormously.”

“It truly was one of the performances in my life, and there aren’t that many, and you will understand when I say it, that we as a group, and certainly I as a composer, experienced the power of music, I mean truly, the power of music to move people to a place, an emotional place of understanding, and rejoicing—acceptance and rejoicing, and that’s what it’s all about.”

Bonus Listening Notes:

-

“Hannibal” opens In the Clearing with a fanfare on lost causes made immortal, per Frost, by the “generous tears of youth and song.” Its brief collective phrases soar, establishing both Fuch’s energetic homophonic choral writing (where all voices sing more or less the same rhythms) and the rising leaping and tumbling motives that characterize the cycle as a whole.

-

In “October,” Fuchs opening motif rises like the sun on a “hushed October morning mild.” Rich homophonic writing that celebrates the ripening of leaves in fall is interspersed with more delicate exposed entrances of single voices as each leaf begins to fall. Through Fuchs’ setting of Frost’s words, we feel the wind, hear “the crows above the forest call,” and yearn for the sun to beguile us, to enchant us, to be “Slow!” in leaving, “for the grapes sake, if they be all.”

-

“November” is a very different poem, even though it too tells of leaves and their fate. Frost first published it in 1939 as “October,” then republished and renamed the poem “November” in 1942, after the US had entered WWII, in a possible nod to Armistice Day. The leaves, like soldiers, “go to glory” but “get beaten down and pasted” by rain, leaving a year of leaves, or a generation, wasted. While again staying primarily homophonic, Fuchs brilliantly captures the colors and double meanings of the poem, through constant shifts of articulation, dynamics, leaping motives, and tumbling rhythmic contrasts, that capture both the migrations of dying leaves and “the waste of nations warring.”

-

In “Devotion,” Fuchs quiet writing pulses with the beautiful image Frost offers of love as a willingness to be “shore to the ocean,” giving us, in the weave of homophonic and alternating voices, both heart beat and waves, “counting an endless repetition.”

-

The alternating repeated patterns continue to cascade through “Stars,” before sweeping into vigorous homophonic lines that flow like snow and wind. Against this landscape, “our faltering few steps” depicted in delicate staccato, are lost in a beautiful if ultimately uncaring, unseeing accumulation.

-

In a wonderful juxtaposition, Fuchs shifts from Frost’s impersonal distant stars to the “emulating,” stars of “Fireflies.” Fuchs’ setting of the word “flies” makes it both noun and verb. The fireflies zip around us, with flashes of light and sound popping out of the staccato texture, as they “achieve at times a very star-like start, only of course they can’t sustain the part.”

-

Kenneth Fuchs found in Frost’s “A Young Birch,” which begins to “crack its outer sheaf…and show the white beneath” an apt metaphor for coming out – in the composer’s words; “what it is to really stand up and be yourself and how challenging that can be … rewarding too.” Whatever you find in Frost’s words, the grace and wit of Fuch’s largely homophonic choral writing in celebrating “the only native tree that dares to lean,“ is undeniable, from the lyricism to the cracking, popping staccato motives that echo “Fireflies.”

-

“Nothing Gold Can Stay” was the first poem Kenneth Fuchs set, long before the rest of the cycle it inspired was premiered during the AIDS epidemic. Like the longing for sun to linger in “October,” or the emergence of “A Young Birch,” this poem captures the poignancy of a moment of transition: “Nature’s first green is gold, her hardest hue to hold.” In the ephemeral beauty of life, a leaf unfurling and becoming itself, there is also the prospect of loss implicit in the change. With its delicate imitative entrances, Fuch’s setting is perhaps more like a madrigal than the rest of the cycle, but here too he contrasts effectively the vulnerability of single voices with more elegiac homophonic lines, “So Eden sank to grief. So dawn goes down to day. Nothing gold can stay.”

—Yoshi Campbell

* * * * *

Ave Verum Corpus, K.681 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1791)

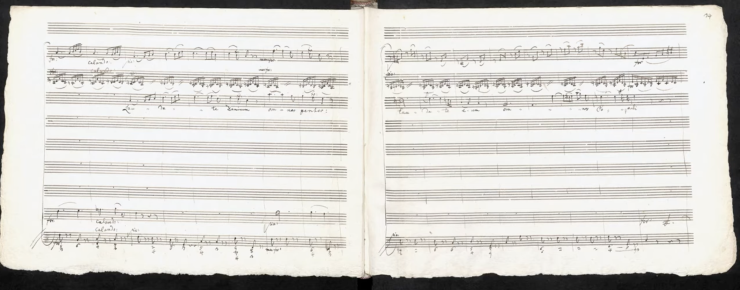

Ave Verum Corpus, K.681, written six months before the composer’s death, is quintessential Mozart, at once simple and complex. Only 46 measures long, and scored simply for strings and chorus, its score comes with a single performance marking in the composer’s hand, “sotto voce” (in an undertone). Its achingly beautiful melody is supported by unusual harmonic shifts and judicious use of chromaticism that elevate crucial moments in the text. The last third of the piece starts very quietly, then gradually builds as it rises slowly in pitch. Only the last line of text is repeated, “in mortis examine” (in the trial of our death). It's as if the rising line, which never gets truly loud, and the poignant chromatic harmonies on the echoed word “death,” yearn for the peace of heaven before settling into calm repose. A brief orchestra postlude gently brings the piece to rest. I can't think of a more beautiful and perfectly constructed work.

— David Hodgkins

Vesperae solennes de confessore, K. 339 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1780)

“Our church music is rather different from that of Italy, and the more so, as a mass including the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, the Sonata all Epistola, the Offertory or Motett, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei, and even a solemn mass, when the Prince himself officiates, must never last more than three-quarters of an hour.” —Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in a letter to his mentor Padre Martini

In 1779, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart returned to Salzburg and patronage of the autocratic Prince-Archbishop Hieronymous Colloredo, following the death of his mother and a failed quest for new musical employment in Munich, Mannheim, and Paris. With his father’s help, Mozart had a better job waiting for him, combining the roles of Konzertmeister and court organist. Yet he wrote: “the Archbishop cannot pay me sufficiently for the slavery of Salzburg.” Much of Mozart’s bitterness was musical. An authoritarian reformer, Colloredo valued efficiency and economy in music. Music written for the cathedral had to be concise, through-composed, with no separate arias, no repetition of text (and no violas). Two years later, the contentious relationship of patron and composer would end in the notorious kick that launched Mozart towards the wider artistic opportunities and uncertainties of being a free-lancer in Vienna. In the intervening years, Mozart wrote much brilliantly expressive church music within the confines of Colloredo’s requirements, including Regina Coeli, the Coronation Mass and two vespers settings, including the1780 Vesperae solennes de confessore, K. 339, his last work for the Salzburg cathedral.

Vespers (from the Latin for “evening”) is a Christian service of evening prayer, and one of the daily services, or Hours, that make up the Divine Office. Vespers composed for the Salzburg cathedral included settings of five psalms plus the Magnificat. These six movements were interspersed with readings and prayers and can be enjoyed as stand-alone pieces. The Vesperae solennes de confessore is written for SATB chorus and soloists, violins, trumpets, trombones to double the lower chorus parts (omitted from today’s performance), timpani, and basso continuo of cello, bass, and organ, with a bassoon obbligato. The word “solennes” (solemn) in the title signifies a work accompanied by orchestra and the name “de confessore,” added by later hands, suggests it was written for a saint’s day (though it’s not known for sure which one).

What we do know is that Mozart was proud of Vesperae solennes de confessore, enough so that he asked his father in 1783, to send the score to Vienna so he could share it with Baron Van Swietan, who had introduced him to Bach and Handel. As David Hodgkins notes, “even though Mozart did not have violas at his disposal, the orchestration never feels thin or incomplete.” Within the confines of 25 minutes of music, Mozart unpacks an extraordinary amount of text. “It’s what I love about Mozart” adds Hodgkins, “the colors, the inventiveness, the ability to say something so profound in such a succinct and clear manner—to understand form and style to such a sublime degree and then take you on a musical journey that in other hands would be pedestrian.”

All six movements conclude with the Lesser Doxology, “Gloria Patri et Filio et Spiritui Sancto.Sicut erat in principio, et nunc, et semper. Et in saecula saeculorum. Amen." (Glory to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit. As it was in the beginning, is now, and forever, and for generations of generations, Amen). Needing to set this same text six times in one work creates a compositional challenge that Mozart embraces. Each instance he writes is different in form and character, and his diversity of invention creates the impression of a multitude of voices like the generations of the text.

“Dixit” (Psalm 110) opens in C Major exuberance. The chorus’s energetic exposition of the text is rich with word painting, from the arresting augmented 6th on "Judicavit in nationibus" (He will judge all nations) to the dramatic rising cadence of "exaltabit caput" (He shall lift up his head).

- The first “Gloria Patri” opens with a brief glorious interjection by the solo quartet, before the chorus returns to sing of time, quietly evoking eternity through the long notes of “in saeculorum” (of generations) before building to a vigorous rhythmic close.

“Confitebor” (Psalm 111) alternates confident unified statements, with imitation, flourishes, and the varied textures of soloists and chorus. Psalm 111’s acknowledgment of an eternal covenant is underlined by a lilting three-note motive on the words “manet” (it endures), which the soloists echo.

- After a unison choral entrance that echoes the opening, the closing “Amens” of the closing “Gloria Patri" repeat this assurance as if to remind us that justice and memory endure.

The triple meter “Beatus vir” (Psalm 112), is almost operatic, in its dramatic shifts of textures, harmonies, and registers. The ascending intervals and scales of the opening chorus frame an extended melisma for the soprano soloist, before descending again through a cycle of 5ths.

- This “Gloria Patri” opens with a leaping ornamented line in the soprano, and then descends on suspensions and scales as the chorus lands on the final cadence.

“Laudate pueri” (Psalm 113), by contrast, is a fugue in the stile antico (ancient style). The subject, with its dramatic descending 7th, foreshadows the fugue from the Kyrie of the Requiem. The counter subject, with its descending scales, connects “the Lord God, Who dwells on high” with the “lowly,” “needy,” and “poor” that the music uplifts.

- In this “Gloria Patri,” the original fugue subject reappears, now mirrored and inverted, with dramatic descending patterns and pauses that bring this striking movement to an end.

David Hodgkins describes “Laudate Dominum” (Psalm 117), as “one of the most elegant, tender soprano solos every written—an aria really—with gentle undulations in the strings, and a simple, yet drop-dead gorgeous countermelody in the bassoon.”

- In the“Gloria Patri” the chorus reprises the melody in graceful congregational harmonies that underlie the text’s promise that the mercy of God belongs to all people

The Magnificat opens in awe. Over a triplet pulse of the strings, the voices enter in dramatic, dotted leaps. The movement balances the pulse of repeated notes, fanfares, and pedal tones conveying the continuity of God’s promise to Abraham and his descendents, with all the extremes of the text—the powerful brought down, the lowly exalted, the hungry filled with good things, and the rich sent away empty.

- The final iteration of “Gloria Patri” opens with the warm interplay of the solo quartet. Then the chorus enters in cannons whose counterpoint builds, before a final cadence that recalls the end of the "Dixit" (as it was in the beginning is now and ever will be, Amen).

— Yoshi Campbell, with gratitude to Gail M. Armondido, Ph.D